A Piedmontese Bookstore

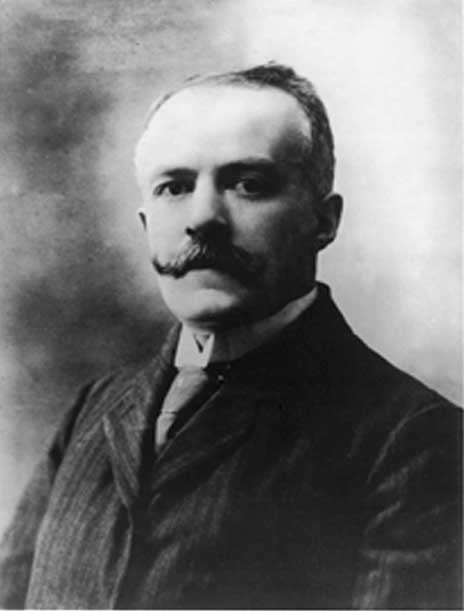

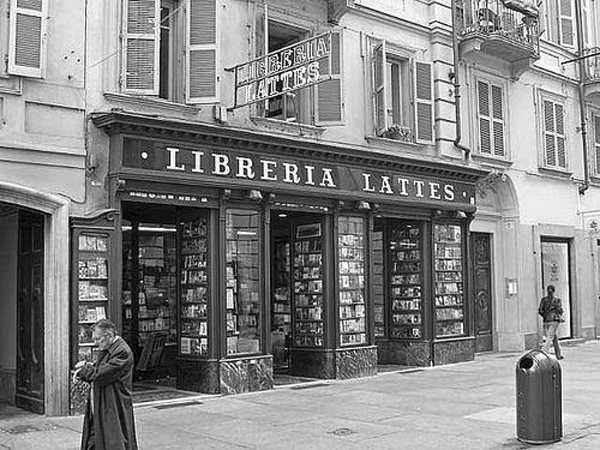

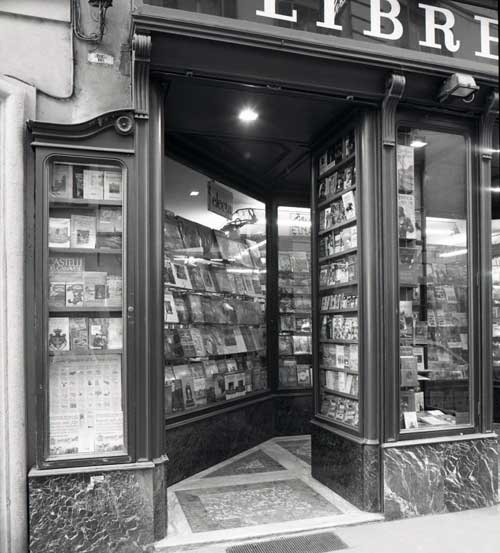

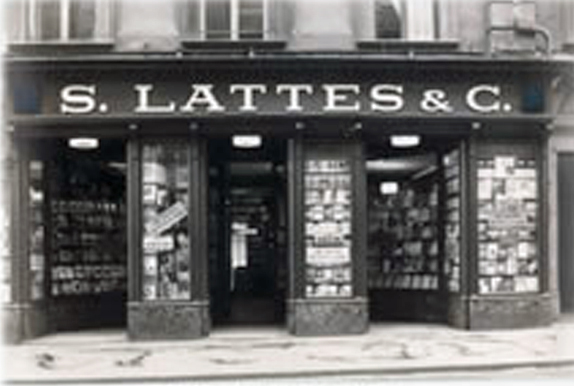

The Libreria Lattes, bookstore and publisher, opened in Via Garibaldi 3, Turin in 1893. It’s founder, Simone Lattes, born in 1862, began working at the Casanova bookstore (today Libreria Luxembourg), acquiring first-hand knowledge of the book market.

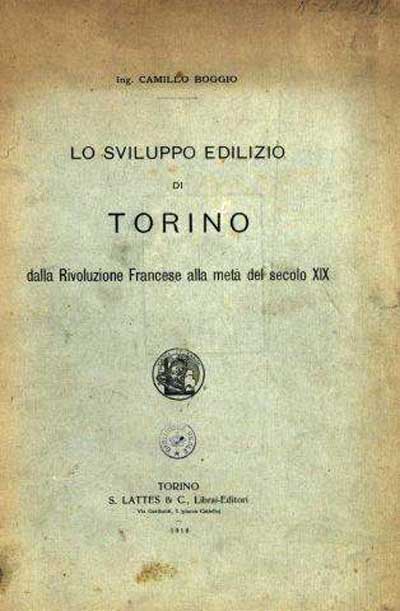

Lattes’ first books were dedicated to Piedmonte, where he was born and where, three centuries earlier, his ancestors had found asylum after the expulsion from Spain. Their last name derived from a town near Montpellier. Like many Piedmontese Jews, the family had absorbed local culture and language, forging a tradition that remained unique among the Jews of Italy. Although ghettos were created in Piedmont in the early 18th century, almost three centuries after the rest of Italy, other forms of segregation and “suspicion” – as Primo Levi described it – separated the Jews from the rest of the population. As the House of Savoy lead the unification of Italy, the Jews of Piedmont were among the first to enjoy emancipation in the peninsula.

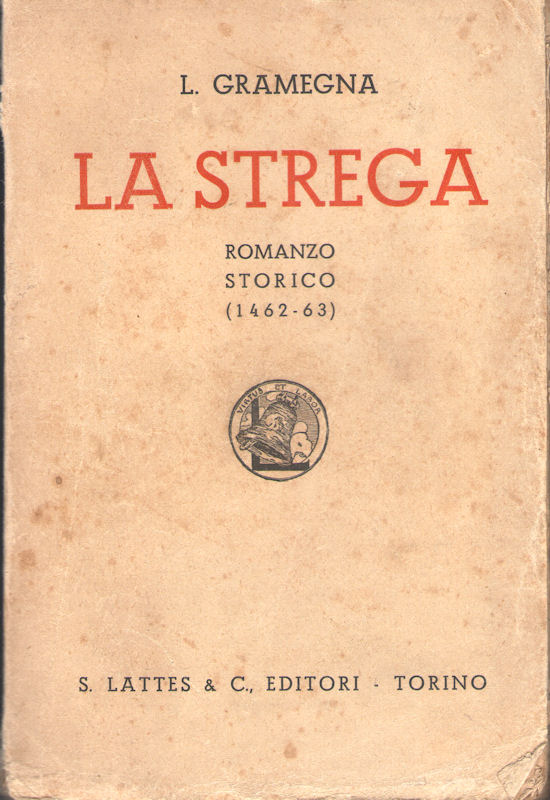

The Lattes publishing house opened in 1896 with the publication of a book on Piedmontese theater and another on eighteenth century Spain. It also published two books on Turinese dialect, idioms and sayings.

Lattes developed the firm along three lines: book publishing, which he expanded with a second bookstore in Via Po and a lending library; distribution; and educational publishing which still remains the house’ main vocation.

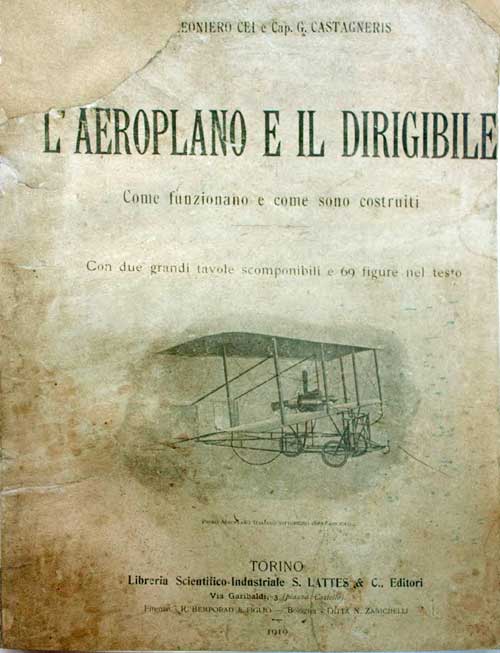

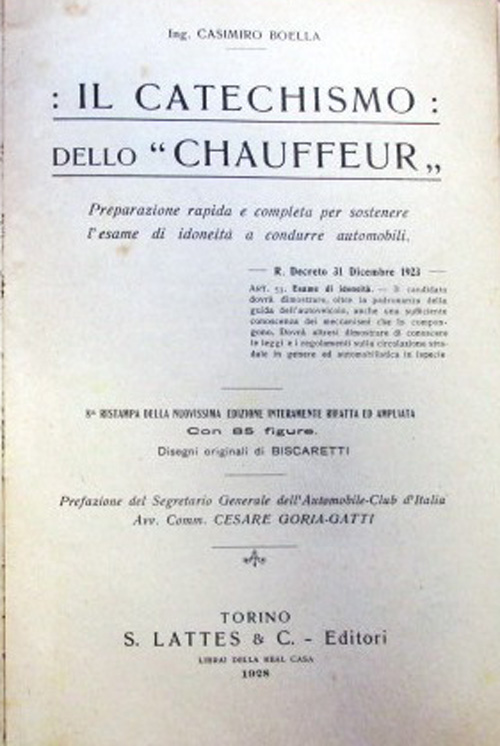

Text books included business and technical manuals, the “Biblioteca tecnico-industriale,” the “Biblioteca di scienza pratica” and “Archivio per le scienze mediche”. In 1908, he also launched a series of contemporary literature that began with Massimo Bontempelli’s novels and short stories collections.

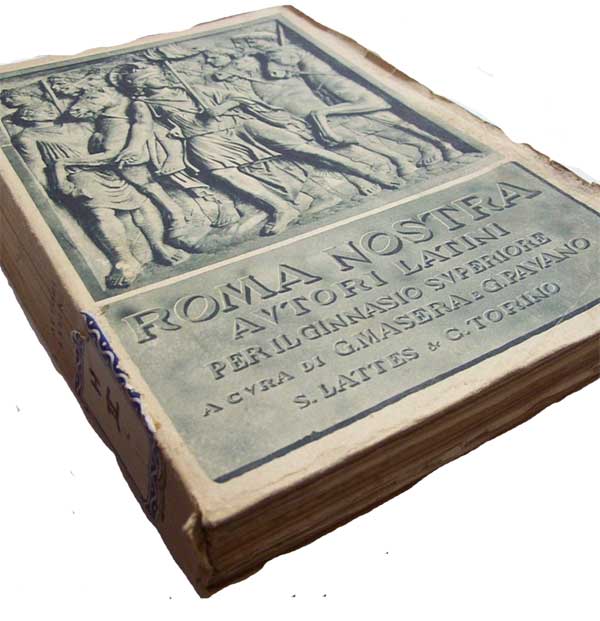

Carefully curated school books spanned from Greek literature and history to geography, algebra, English and French grammars, bookkeeping, statistics and mathematics.

A German-Italian/Italian-German Military Technical Dictionary and several volumes on international relations reflected the political and diplomatic events of the Great War.

New Company

In 1918, Lattes created the Società Anonima S. Lattes & C. of which he became managing director. The president was Enrico Bemporad, owner of the Florentine publishing house by the same name, whose editions were distributed in Piedmont and Liguria by Lattes.

Bemporad encouraged Lattes to purchase some shares of Giulio Cesare Sansoni publishing house.

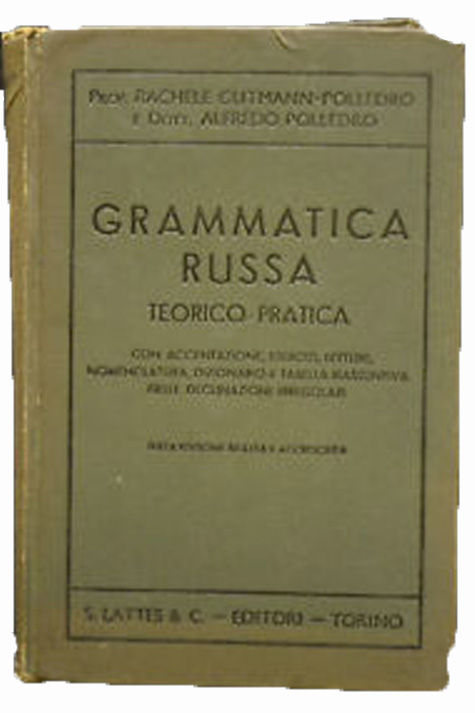

Within five months of its constitution, Lattes, launched forty-two titles including new books and reprints. Topics ranged from navigation and maritime science, agronomy and medicinal plants, critical essays on D’Annunzio to a Russian grammar and anthology.

In 1920, Lattes purchased the Boeuf bookstore in Genoa. The bookstore of Via Po took the name of “Libreria internazionale universitaria”.

Under the influence of Simone’s son, the physician Ernesto Lattes, the firm started a scientific magazine “La medicina sperimentale italiana” as well as a series of children’s literature.

School book production continued to grow with texts ranging from the history of commerce, radiotelephony, botany, as well as specialized texts for higher education.

School Reform

In 1923, Giovanni Gentile’s school reform began to standardize the national school system to match the views of the rising dictatorship. This rendered many existing book unusable thus severely impacting their publishers.

Unlike most publishers, Lattes did not have a large stock of unsold books and did not depend solely on the Ministry of Education, but also on technical and trade schools, which at that point were not affected by the reform. He was therefore able to adapt its catalogue to the changing school system.

Simone Lattes died in 1925 and his son Ernesto took control of the firm along with Romano Bozzola.

The bookstores in Turin and Genoa were sold and the the circulating library suspended. Ernesto Lattes also sold the Sansoni shares and ended the distribution of their books.

The publishing house moved back its old building in via Garibaldi, above the bookstore. Bemporad resigned from the presidency and was replaced by Ernesto Lattes.

In 1931, the Lattes publishing house revived the original interest in Piedmontese culture with several guidebooks. In the same year, it began the publication of the magazine “L’ Architettura Italiana,” which continued until 1941. In 1935, Lattes also published a new Dictionary of the Italian language.

The Racial Laws

The 1930s where a trying period. Ernesto died and a second school reform (the Bottai Reform) set a new standard in the Fascist repression requiring full adherence of textbooks to the regime’s objectives. For publishers, to conform, entailed huge investments.

At the same time, with the promulgation of the racial laws, the firm was forced to remove its Jewish name as well as it Jewish staff and ownership. The name was changed to Editrice Libreria Italiana (ELI) and Vittorio Preti was nominated director. The administrators, Ferruccio Colonna and Fernando Valobra, were forced to resign because of their Jewish descent.

The bombings of 1942 and 1943 destroyed plants and paper stocks, preventing reprints of numerous titles. Offices, warehouses and personnel were transferred to Bobbio Pellicle in one of the Piedmontese valleys. In 1944, the authorities of the Italian Social Republic confiscated the company as Jewish property.

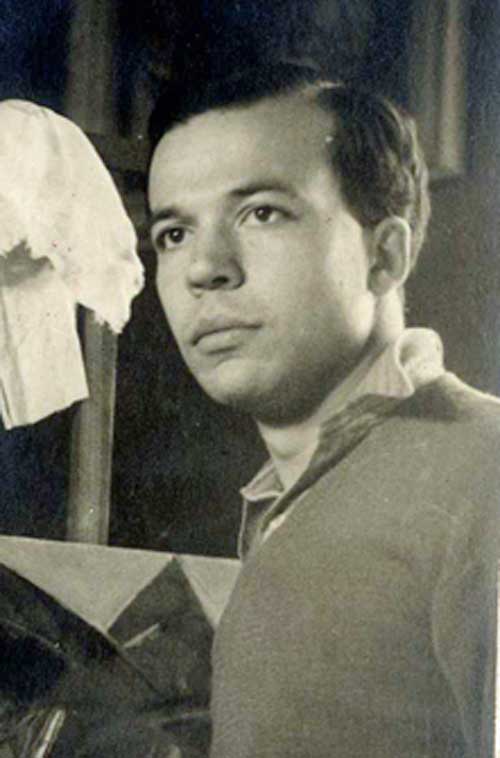

Mario Lattes, the young heir of the publishing house, went into hiding. Thanks to his command of English, he found employment as an interpreter with the British army that stationed him in Rome. He later described these months in a novel entitled Il borghese di ventura (Einaudi).

After the War

At the end of the war, Mario Lattes reclaimed possession of the publishing house, reinstated the name and moved back to Turin. The damages caused by the racial laws and the war were never compensated and the first years were difficult; the bookstore passed in the hands of Librerie Riunite.

In 1949, twenty-six year old Mario Lattes was appointed chairman of the company. Five years after the end of the war, the publishing house had regained stability. Its focus remained on textbooks while it launched new cultural initiatives and – in reaction to twenty years of isolation – introduced a series of books in translation.

Mario Lattes opened a new space combining the publishing house with an art gallery. Visual arts were his passion and he was himself a successful painter. In collaboration with Oscar Navarro, Albino Galvano, and Vincenzo Ciaffi – he created the bi-monthly magazine “Questioni” which, until 1960, provided access to 20th century’s Italian and foreign literature publishing essays and poetry by Adorno, Abbagnano, De Libero, Vittorini, Levi, Turf, Sanguinetti, Pandolfi, Dorfles, Mollino, Holthusen, Tardieu, Ionesco, and Adamov. After ten years of intense activity, the magazine closed with a monographic issue dedicated to Robert Musil.

In 1963, a new school reform rattled the publishing world. Lattes reinvented its catalogue introducing a new approach to education. Teachers embraced Lattes’ policies and choices.

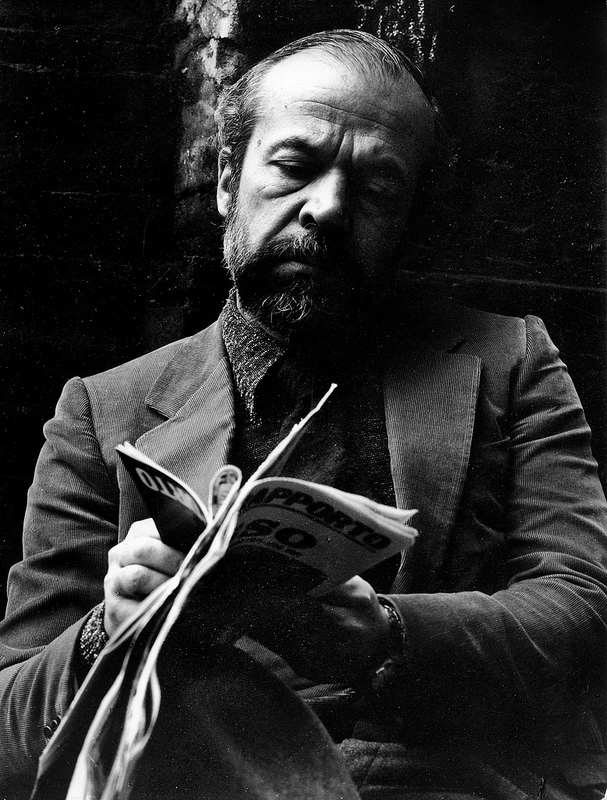

During the 1970s, Lattes continued to follow educational reforms as well as the country’s political turmoil. Between 1973 and 1977, he created a semiannual newsletter providing information and counseling for teachers.

In 1976, the oil crisis and the rising cost of paper on the one hand and the reform debate on the other – forced the firm to suspend new titles for a year. Mario Lattes wrote an editorial in his newsletter explaining the reasons for this choice: “reflection is needed, for publishers are not merely manufacturers of books, but care for each textbook, and the meaning of its presence on every teacher’s and pupil’s desk”.

Following the school reform of 1979, Lattes published new text books reflecting broader views of the world. In 1993, the publishing house celebrated its centennial with a catalog devoted entirely to school books including a new guide for young library users illustrated with watercolors by Mario Lattes.

Lattes died in 2001 having left the publishing house to his daughter Renata who ushered it into the digital age.