A Love for Italy

The long history of the Leo Olschki publishing house dates back to 1883, when Leo Samuel Olschki, the son of a typesetter who worked in the small town of Johannisburg in East Prussia, decided to follow in the path of many other members of the ultramontane book trade — Rosenberg & Sellier, Sperling & Kupfer, Hoepli, Rappaport, Bretschneider, Le Monnier, Loescher, Scheiwiller — and relocate to Italy.

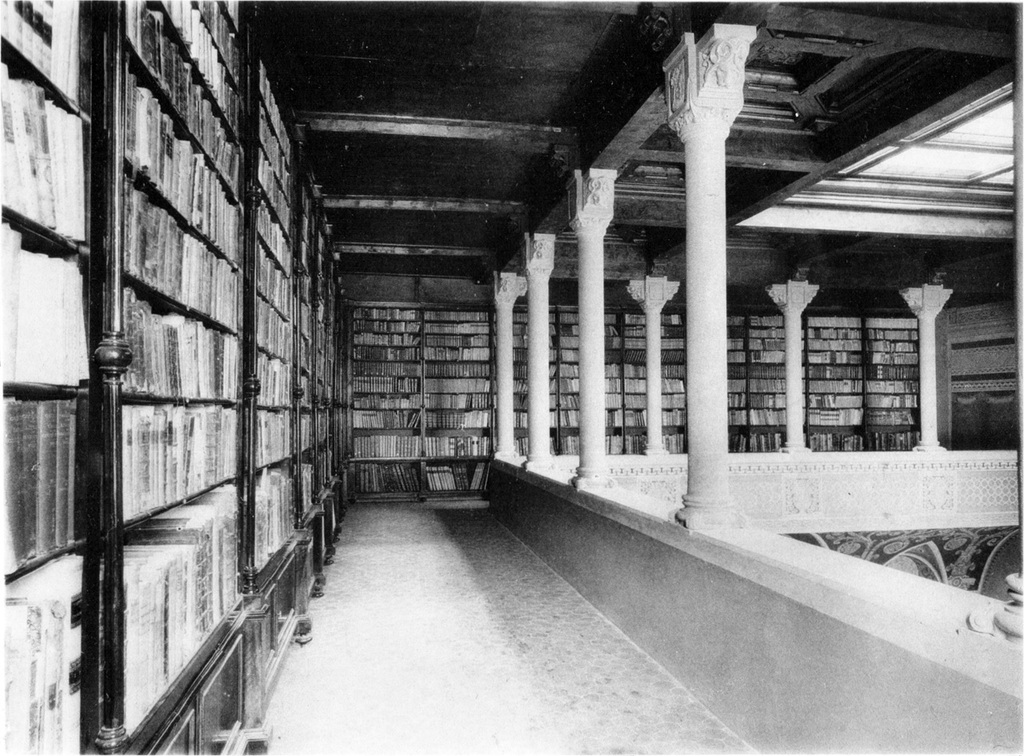

Each of them was drawn by the dream of becoming a publisher in Italy — of founding a firm that might prosper well in the lively intellectual atmosphere of a recently unified Italy. Leo settled in Verona where, after a brief apprenticeship with a local bookseller, he founded his own antiquarian bookshop and publishing firm in 1886.

The new business was initially confined to the antiquarian side, which soon flourished thanks to Leo’s ability to identify and evaluate rare books – especially incunables and XVIth century editions. He quickly established himself as a leading figure in the antiquarian trade. Leo’s command of foreign languages — he knew seven, including Latin and Greek — not only ensured his international success with scholars and collectors, but gave a broad reach to his publishing arm.

In 1889, he founded L’Alighieri, a journal devoted to the great poet who remained Leo’s chief passion. Dante remains a touchstone of the firm to this day. In 1890, he moved to Venice, where he spent the next seven years. In 1897, he decided to move permanently to Florence. Although Olschki did not neglect the antiquarian business, his publishing branch now assumed an increasing importance. Leo launched several new series of books on literature, linguistics, and above all bibliography, his favorite subject, as exemplified in the periodical La Bibliofilia (1899) and a series of manuscript catalogues, the Inventari dei manoscritti delle biblioteche d’Italia. In 1909, Leo established the Giuntina, a printing firm that could offer a level of typographical excellence to match his great editorial enterprises, such as the monumental edition of the “Divine Comedy” (1911) to which Gabriele d’Annunzio contributed a long introduction.

The outbreak of World War I brought a dramatic reversal to Leo’s fortunes as anti-German sentiment spread throughout Italy. Leo’s Prussian origins led to his being accused of espionage on behalf of the Kaiser. He was driven into exile in Geneva, where he established a branch of the Florentine firm. With the conclusion of the war, he returned to Italy and managed to carve out a place for his sons in the business, encouraging Cesare to pursue the antiquarian trade, and Aldo to devote himself to publishing.

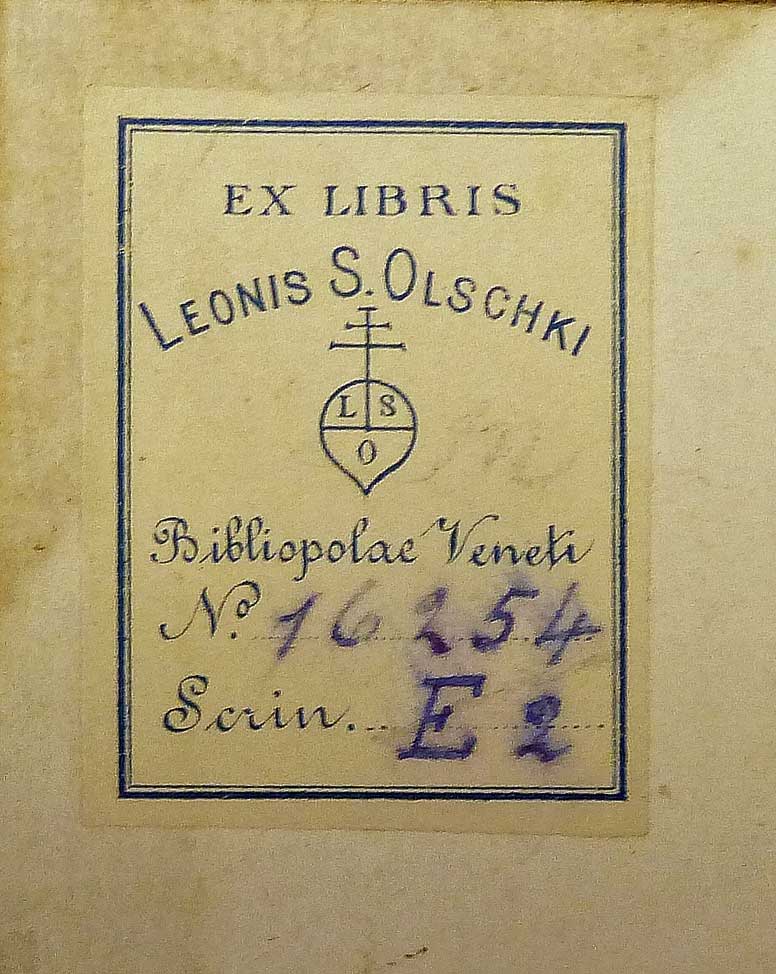

But there were further trials ahead for Leo. In 1938, the anti-semitic Manifesto of Race again forced him into exile in Geneva, where he died on June 17, 1940. Meanwhile his sons Cesare and Aldo were forced to divest themselves of the Giuntina press and to publish only in semi-clandestine form under the name «Bibliopolis». They nonetheless succeeded in preserving the Olschki insignia intact by means of their brother Leonardo’s ingenious interpretation of the patriarch’s initials (Leo Samuel Olschki) as an acronym of the motto “Litterae servabitur orbit”.

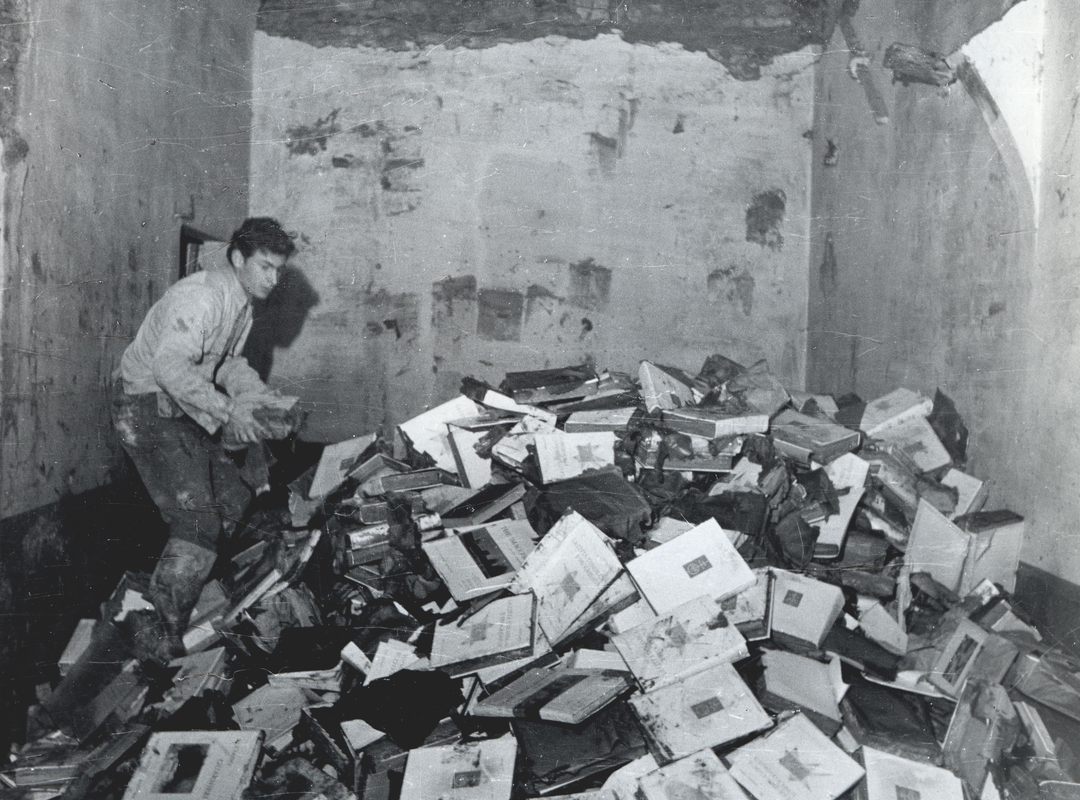

During the war, the Florentine headquarters was destroyed burying a great part of the rare book inventory, the firm’s publications and the editorial archive. The bookshop on Lungarno Corsini was also destroyed. Everything seemed lost, and to make matters still worse, disputes arose between the two brothers, leading to a division of the firm in 1946 along the lines already laid out by Leo. Cesare took over the rare book business, while Aldo continued to manage the publishing house. Among the company assets were precious incunabula, and such treasures as the famous “Codice Musicale Mediceo”. Although weakened by asthma and generally poor health, Aldo endeavoured to re-establish the business, adding books on the subjects he loved to the firm’s list. These included works on musicology, the history of science and archaeology, with a particular focus on Etruscan studies.

Among the new journals that were founded or migrated to Olschki in the postwar years were Belfagor and Lettere Italiane which became very important in the Italian cultural world. Leo’s journal La Bibliofilia continued publication, along with Biblioteca di Bibliografia italiana and Inventari dei Manoscritti delle Biblioteche d’Italia. These new magazines interpreted and brought into modernity the idea shared by many 19th century Italian publishers to bridge the worlds of publishing, education and libraries.

Postwar

Alessandro was heir to an almost impossible situation. The financial support of the antiquarian side was a thing of the past, and he was expected to maintain the publishing business on his own. His stroke of genius was to transform our firm into the publishing branch of the most important cultural institutions of Italy. Under his direction many new partnerships were established — with the Fondazione Cini, the Accademia Colombaria, the Deputazione di Storia Patria per la Toscana, the Società di storia del Risorgimento, the Centro Nazionale di Studi Leopardiani, and the Istituto Nazionale di Studi sul Rinascimento. The company recovered, and in the mid-Sixties production soared. Each year, the number of new publications was double the total amount published during the entire postwar period.

The inventory was destroyed again during the flood of 1966. In 1969, the Olschki firm opened its new headquarters in “Il Palagio”, a XVIth-century villa in viuzzo del Pozzetto, where it remains to this day. In the early Seventies, the cultural range of our publishing house expanded with the introduction of yet more series. The number of new titles issued per year rose to around one hundred, requiring increased editorial attention.

Alessandro’s burdens were eased by the arrival of a fourth generation of Olschkis in the company. To Daniele and Costanza was assigned the task of improving standards of quality and of initiating new partnerships. That single decade brought enormous technical changes — indeed, the total revolution of a system of production that had remained unchanged for almost a century. A craft that had relied on the impress of lead and the transmission of skills from one generation of typesetters to the next seemed to have vanished overnight.

With some reluctance we began to experiment with photocomposition and offset printing, attempting to maintain the high typographic standards of the past, while at the same time improving the quality of paper, binding, and printing. Time refuses to stand still, and at the beginning of the 21st-century the company faced a second revolution: that of digital books.

With a 127-year history, Olschki has succeeded in overcoming setbacks and disastersand has preserved the publishing house as a family concern, maintaining the original commitment to the finest humanistic scholarship.