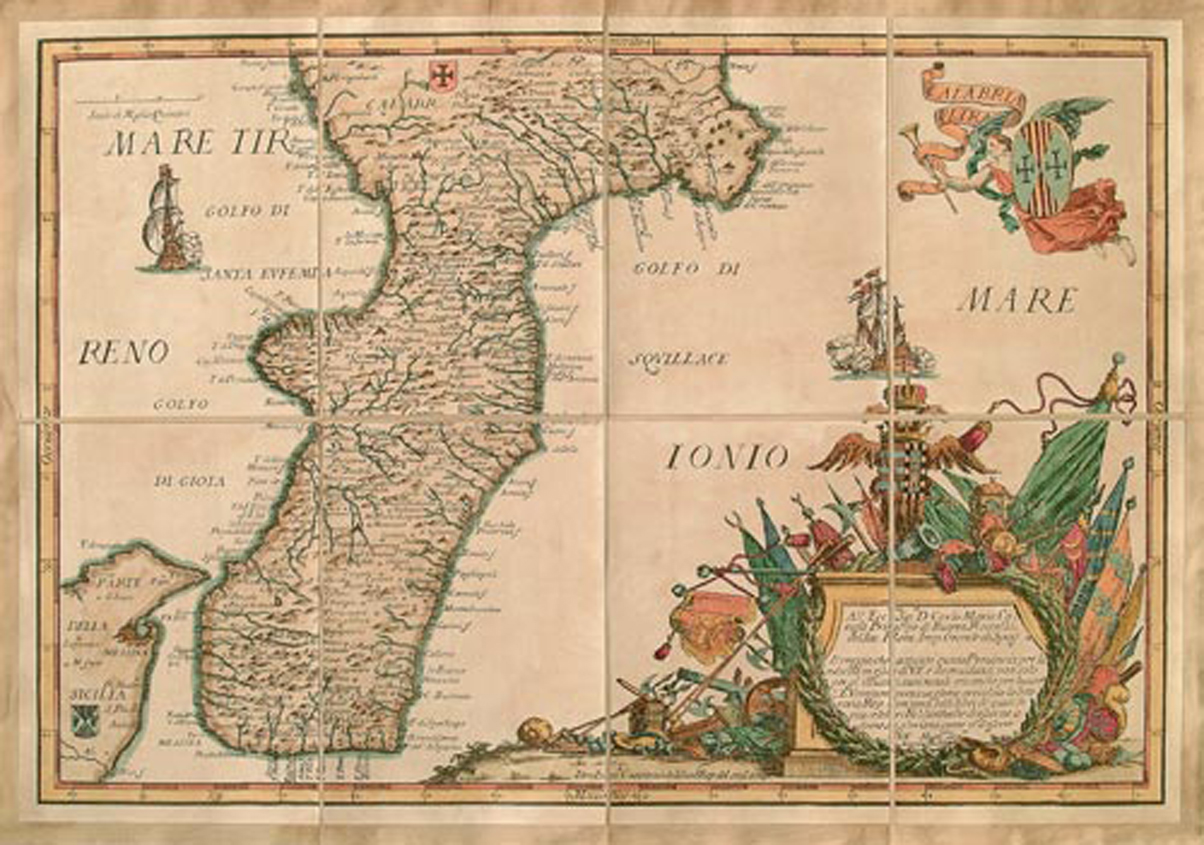

Medieval Jewish chronicles attribute the beginnings of Jewish settlement in Calabria to captives exiled by Titus after the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E. However, there is no concrete evidence proving that Jews were present in Calabria until the first half of the fourth century. We do know that the Calabrian community became prosperous around this time, and was the object of envy and complaints during the reign of Emperor Honorius (398 C.E.).

The archeological remains of a synagogue dating to the fourth and fifth centuries were discovered in Bova Marina, located in the southern coast of Calabria. The central hall has a niche with a bench and a mosaic floor where the designs of a menorah and a Salomon’s knot can still be discerned. In the early 10th century, Calabria was devastated by Arab raiders. The Jewish population of the region was one of the communities most impacted. However, soon afterward, the position of the Jews improved both economically and culturally. Scholars of Calabria were in touch with Hai b. Sherira (Gaon) in Mesopotamia in the 11th century. In the 13th century, the silk industry and other state monopolies were in Jewish hands, mainly owing to the protection afforded by the emperor Frederick II.

Following 1288, under the reign of Charles II of Anjou, persecutions and attacks were fomented by Dominican friars in Calabria, as in the rest of the kingdom. About half of the 2,500 Calabrian Jews were forcibly converted to Christianity. Later, the community recuperated and expanded; in some towns, the Jewish population is said to have outnumbered the Christian. Calabrian Jews enjoyed economic prosperity under the Aragonese dynasty, until 1494.

The fairs of Calabria attracted large numbers of local and foreign Jews. In 1465, the Jews coming to the fair of Maddalena di Cosenza obtained the privilege of having to answer only to the king’s official and to no other person in charge of the market. In 1481, King Ferrante I promulgated a series of laws regulating the status of the Jews in his kingdom. The communities of Calabria were granted the following privileges: they were not to be subject to the jurisdiction of city officials; they could address themselves to any notary or judge they chose; they would be taxed only according to the actual number of households; no Jew would be exempted from taxation, except the king’s physician.

In 1480–81, when the Turks attacked Otranto, Jews throughout the kingdom were forced to pay substantial sums to the treasury. The Jews of Calabria alone were taxed 2,600 ducats. However, the heavy taxation of the 15th century caused some Calabrian Jews to migrate to Sicily.

Several Hebrew manuscripts are known to have been copied in the cities of Calabria during the 15th century. Rashi’s commentary to the Pentateuch was printed in Reggio di Calabria in 1475 and is the first dated Hebrew book to have been printed in the Kingdom of Naples. On the expulsion of the Jews from Sicily in 1492, many refugees arrived in Calabria, most of the Syracuse community coming to Reggio di Calabria.

After the expulsion, the Jews of Calabria maintained commercial and personal relations with New Christians in Sicily. Calabria also served as a refuge for New Christians from Sicily fleeing the Spanish Inquisition. After the region passed under Spanish rule, persecution of the Jews in Calabria was renewed, and in 1510 they were all expelled from the region, including New Christians. Some migrated to central and northern Italy, and others to Salonika, Constantinople, and Adrianople, where they founded their own congregations and synagogues.