Origins

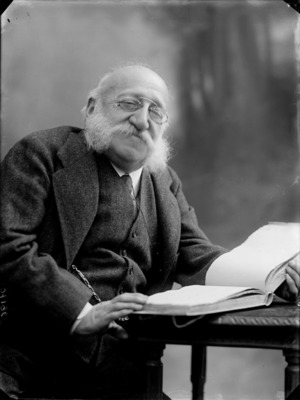

The Treves publishing house was founded by Emilio Salomone Treves, son of Sabato Graziadio Treves, chief rabbi of Trieste, and Lia Montalcini. His father taught at the local university and was considered a man of modern and enlightened views.

Emilio was born in 1834, a time when northern Italy was still under the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He attended both public school and Hebrew school and, at an early age, began his writing career with a play entitled Ricchezza e povertà, composed between 1848 and 1851.

In 1853, he published a historical drama in five acts: The Duke of Enghien. The choice of subject was not without significance; the Bourbons’ claim of rights could be read between the lines as a statement of support for the restoration of Italian rule over Trieste. The book was published, but the production of the play was censored.

During the same year, Emilio’s brother was convicted for possession of propaganda pamphlets against the Austrian government. In those years, patriotic journalism in Trieste was mostly underground. Although he never came to any direct confrontation with the authorities, Emilio was indirectly involved. Considered “rebellious” and too close to anti-Habsburg circles, in the spring of 1854, he decided to move to Paris, where he taught Italian and worked on an Italian-French dictionary.

Europe

Paris, sizzling with literary and artistic activities, was congenial to Emilio’s nature; he loved salons, theaters, literary cafes, publishing houses and printing presses. He absorbed the dynamics of intellectual and political life, and learned the art and craft of journalism and publishing. The French capital proved crucial to his future profession as publisher. He was impressed with the magazine Musée de Famille, which inspired his first publication upon returning to Milan.

Rav Treves died in June 1856, and in the autumn of the same year, Emilio returned to Trieste. He tried his hand at journalism, founding with Giuseppe Corradi a periodical entitled L’ Anello, which was partly literary magazine and partly dedicated to news reports.

On November 17, 1856, the periodical featured a long article in which Treves exposed the idea that accompanied him throughout life: the importance of of educating all classes of society.

The magazine’s democratic bent must have alarmed the police, as both the first and second edition of L’ Anello were seized by the censorship agency. After fifteen issues, on December 29, Emilio left the newspaper. It is unclear whether this was voluntary or under external pressure.

In early 1857, he wrote to Carlo Tenca, editor in chief of Il Crepuscolo in Milan, offering his services as a correspondent from Paris, probably because the Austrian police had him under surveillance. However, he was called back to fulfill his military duties.

Treves spent time in Trieste and then in Fiume, where he worked briefly in Giovanni Spagnolo’s publishing company, and finally in Udine working as tutor. Torwards the end of that year, or perhaps already in 1858, Treves arrived in Milan, with the intention to return to Paris. Instead, he remained in the city, first as a private tutor for the Marpurgo family, and then as a contributor to the Gazzetta Ufficiale.

Milan

In Milan, the 24-year old Emilio Treves began an influential career in the world of journalism and publishing.

In 1857-58, he was hired by the Gazzetta Ufficiale di Milano where, initially appointed as a translator, he began to write about literature, art, and European politics. He soon became known as one of the most vibrant journalists in town.

Soon the Gazzetta di Milano became too constricting for his ambitions and he decided to take the reins of Uomo di Pietra, a literary and humor magazine founded in 1856, for which Treves wrote under the pen name “Piovano”.

He finally agreed to become political editor of the Gazzetta d’Italia. After a test copy containing one of Treves’ articles reached Vienna, the censorship office suppressed the publication.

Following the political events and fascinated by the figure of Giuseppe Garibaldi, in 1859, Treves enlisted in the Hunters of the Alps, reaching the rank of sergeant. He then joined Garibaldi’s troops and participated in military operations against the Austrians.

A Useful Library

At the beginning of the 1860s, he returned to Milan to finally set up his own publishing enterprise. His first small venture was located in via Durini 29 and was named Editori della Biblioteca Utile. He created his first magazines, the weekly Museo di Famiglia (inspired by what he had learned in Paris), and Annuario scientifico. The printing of both was outsourced to the press of Federico Agnelli.

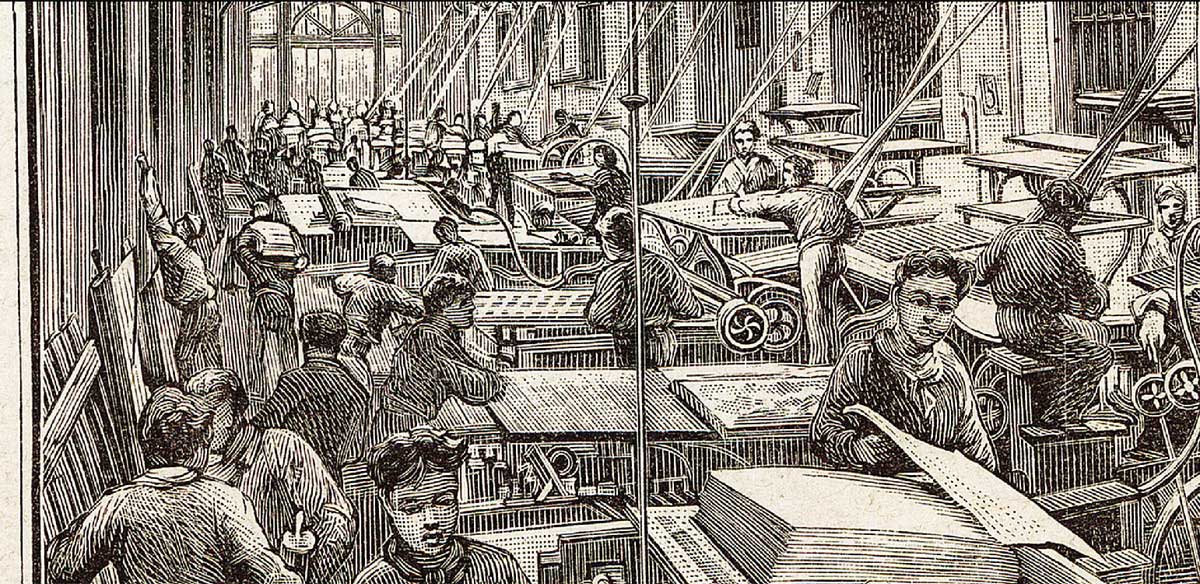

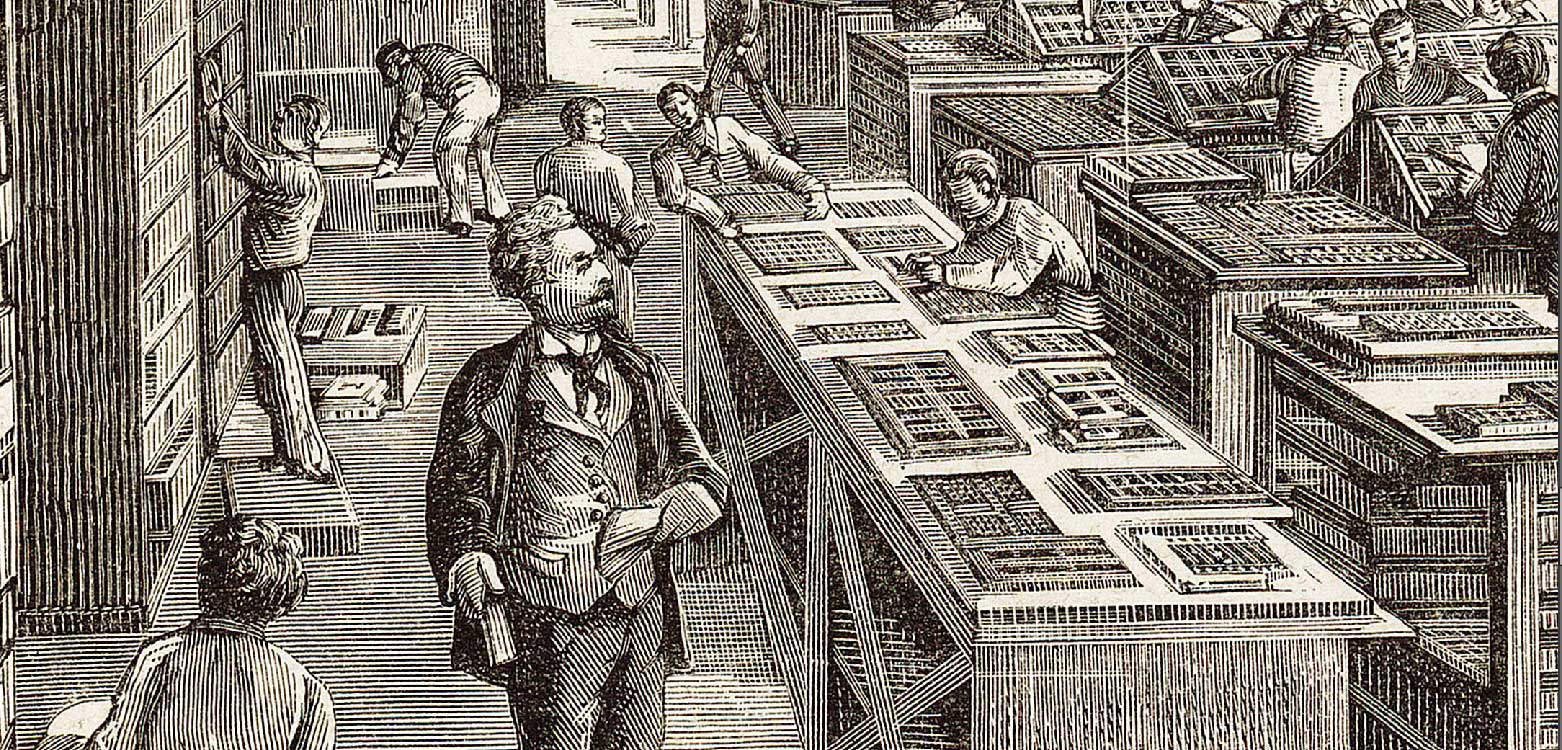

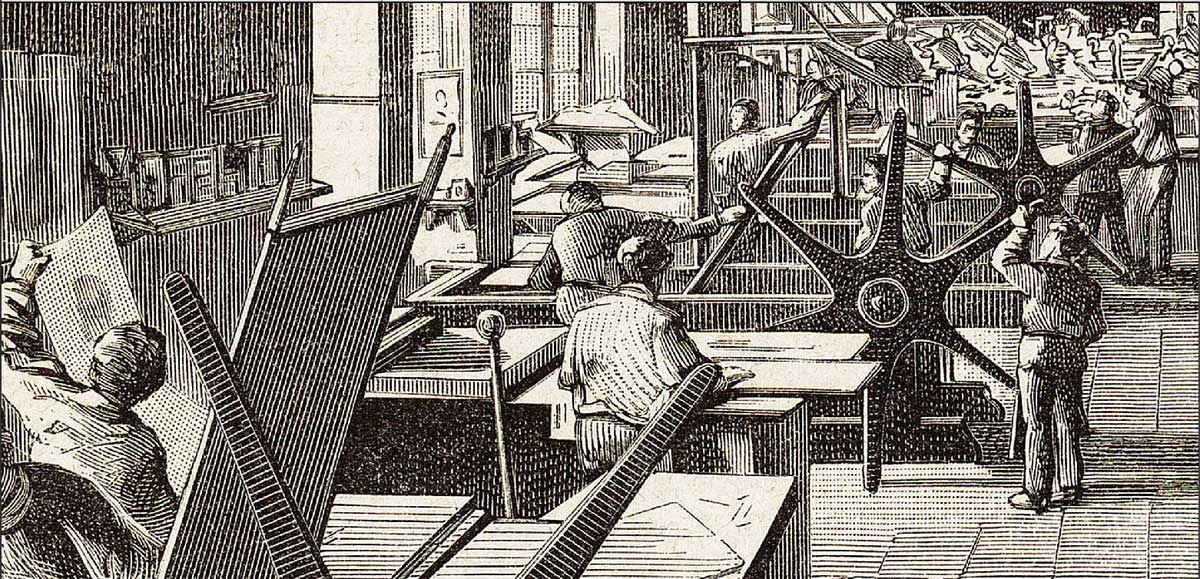

Soon after, Emilio decided to acquire a press for his own imprint. A local printer, a Hungarian refugee named Helphy, was selling his presses as he prepared to leave Italy. In May 1868, Treves took over Helphy’s printshop in via Solferino 11.

The company launched magazines and books: the “Libreria Amena,” L’Universo Illustrato, Il Romanziere Illustrato, Il Giornale dei Viaggi. Treves wanted to offer a large audience access to literature and travel books.

Among the publications that took shape in Treves’ early firm was the newspaper Corriere di Milano, which operated from 1869 to 1874, and whose editor in chief, Eugenio Torelli Viollier, later founded the Corriere della Sera which remains, to this day, a leading national newspaper.

Fratelli Treves and Cordelia

In 1872, Emilio’s brother, Giuseppe, officially became a partner in the company. Giuseppe had worked in Germany and in America, where he acquired business skills. The publishing house was renamed “Fratelli Treves”. Giuseppe invested his savings and the dowry of his wife, Virginia Dolci Tedeschi, who wrote under the pseudonym “Cordelia”.

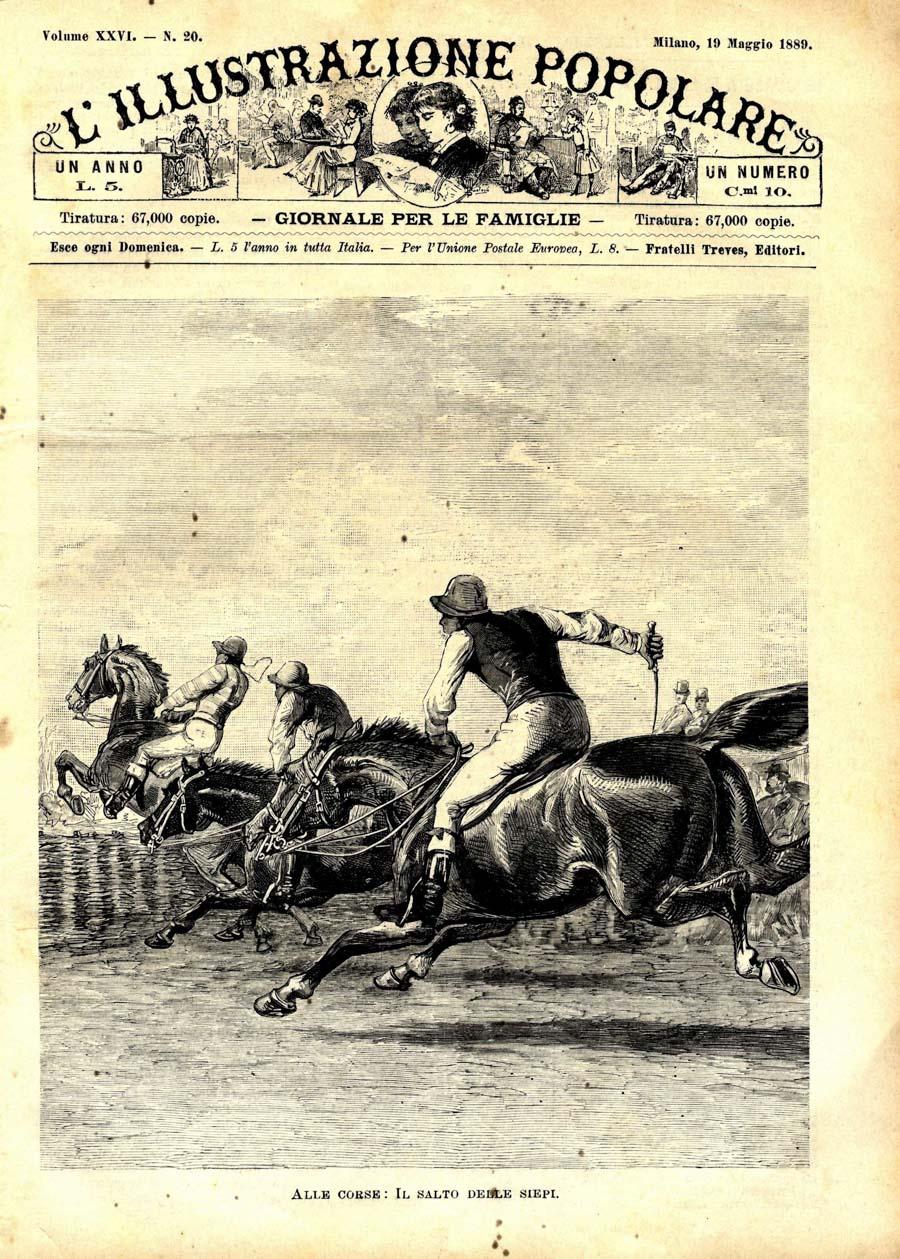

The Treves brothers decided to create an illustrated weekly newspaper of large format, reflecting the aspirations of a unified Italy, in the fashion of magazines already popular in London, Paris and Madrid. A few years earlier, the publisher Sonzogno had unsuccessfully attempted a similar project.

Italy in Words & Pictures

In 1873, the Treves brothers launched La Nuova Illustrazione Universale, renamed L’Illustrazione Italiana in 1876. Throughout the following century, the magazine became a mirror of a new Italian nation.

L’Illustrazione was one of the first magazines in Italy to make use of photographs and remained in print until the 1960s. It offered a gallery of contemporary writings, cultural and political figures, history, public and social life, science, fine arts, geography, travel, theater, music, and fashion.

Treves used to say that, being a weekly, l’Illustrazione had the obligation to be free of the errors that burdened the daily newspapers.

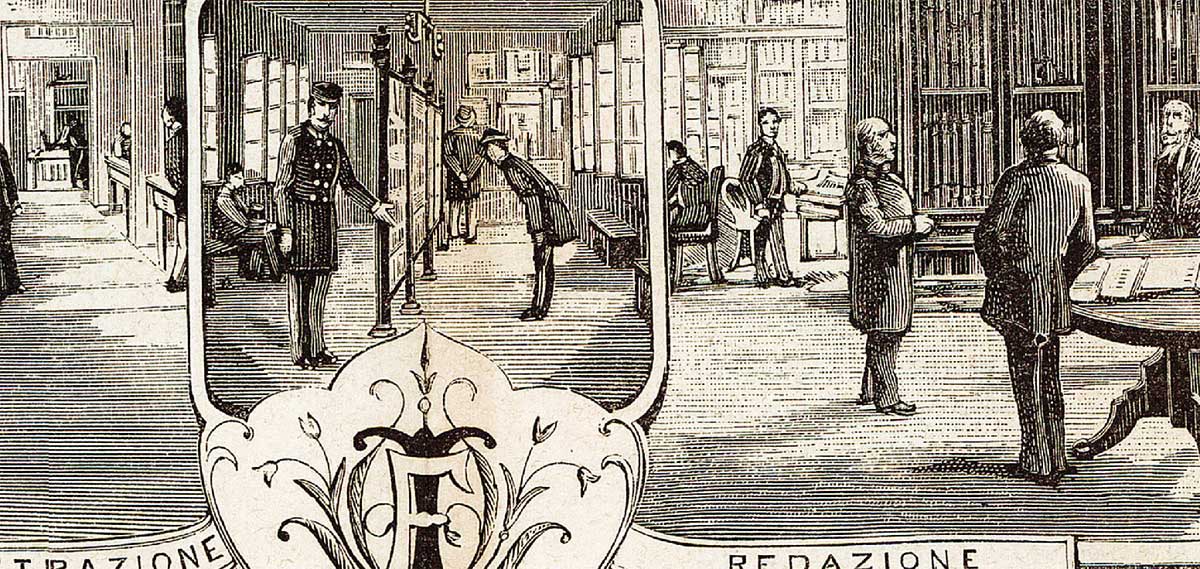

L’Illustrazione Italiana became the firm’s main publishing activity, so much so that, in 1881, the headquarters were transferred from Via Solferino to a larger building in Via Palermo 12. In that year, Milan hosted the World Fair. For the occasion, Treves brothers created a tabloid entirely dedicated to the Fair entitled Milano e l’Esposizione, that covered the activities from the opening day to the end.

Secular Values

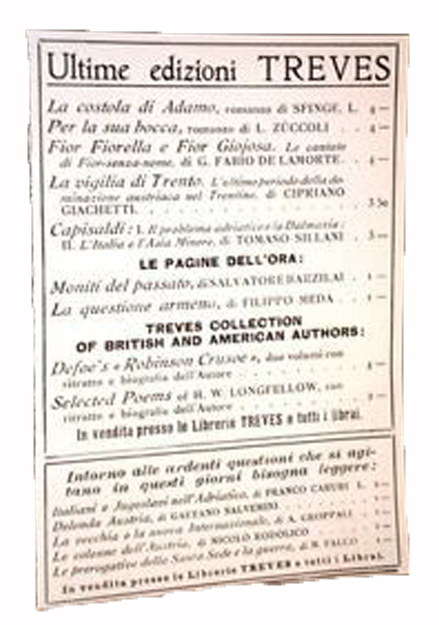

Over the years, the Treves brothers built their company to be a national cultural reference, becoming one of the most visible publishers in the country. They did not want to be only newspaper publishers and slowly started to release books. They created a catalogue of highly selected titles directed at a wide audience, and featuring history, art, politics, school texts, theater, illustrated books, poetry, and fiction.

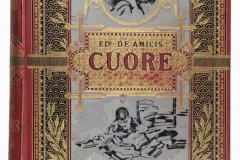

When, in 1885, Gabriele D’Annunzio submitted his first novel, Il Piacere, the Treves brothers were already a showcase for the most acclaimed Italian writers of the time. They also published Edmondo De Amicis’ Cuore, which forged national consciences on secular values, often eliciting condemnation from the Church. De Amicis shared with Treves a past as a journalist and a soldier in Garibaldi’s troops.

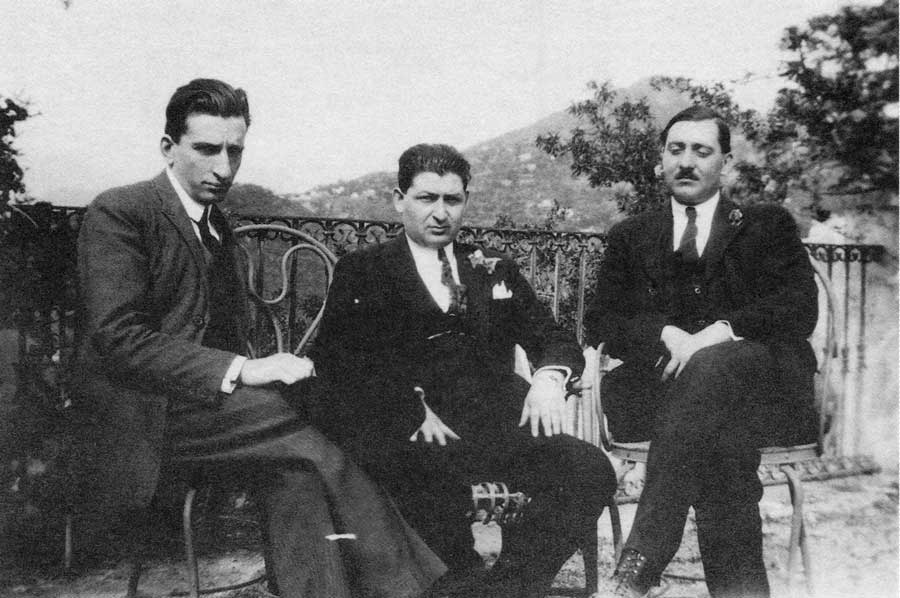

In September of 1904, Giuseppe Treves died, and Emilio formed a limited company, which he managed with great skills. In 1905, his nephew Guido Treves, son of Enrico, entered the publishing house, initially in the administrative office, and then, as co-director of L’Illustrazione Italiana. Emilio did not want Guido to be drafted in Africa, where he had already been in 1903 for the Italian Colonial Society, and insisted that he worked with him.

Guido found himself at ease in the publishing world, having had journalistic experience, and he actively took part in the life of the firm. After Emilio’s death, he took over the reins of the publishing house, together with Giovanni Beltrami. Guido opened his home to scholars and artists, becoming a friend of D’Annunzio, who chose him as best man at his second wedding. Beltrami died in 1926 and Emilio found new partners: Emilio Bestetti and Calogero Tumminelli. In 1931, they created a new company called Treves-Treccani-Tumminelli.

New York and Buenos Aires

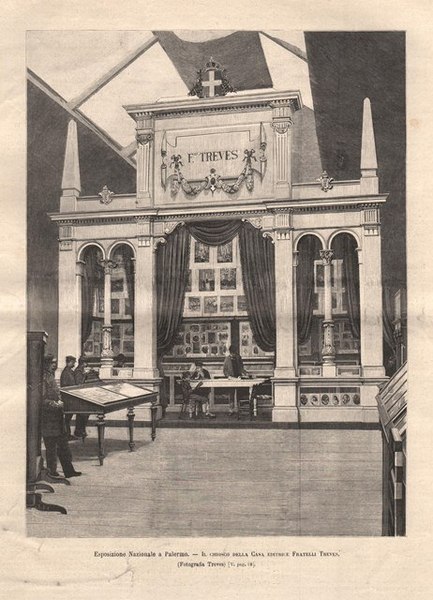

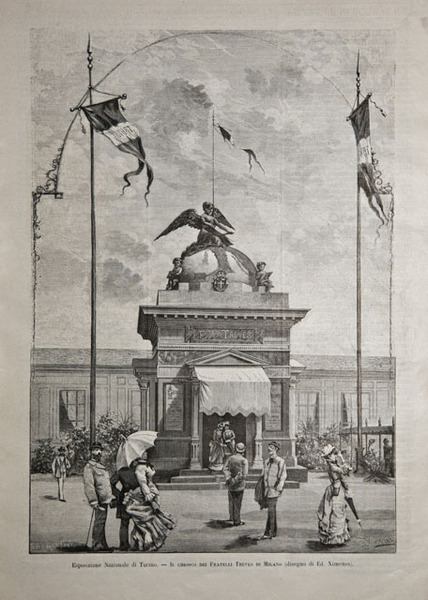

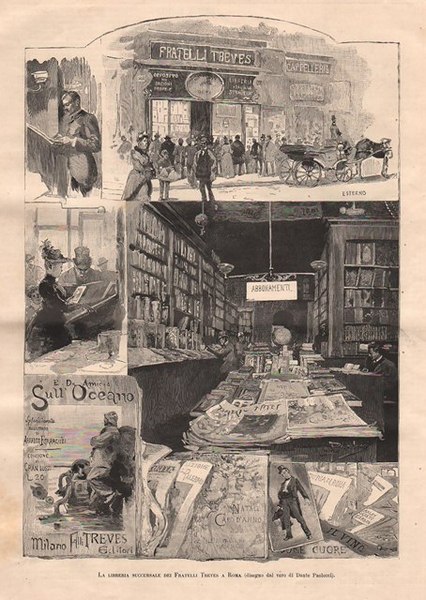

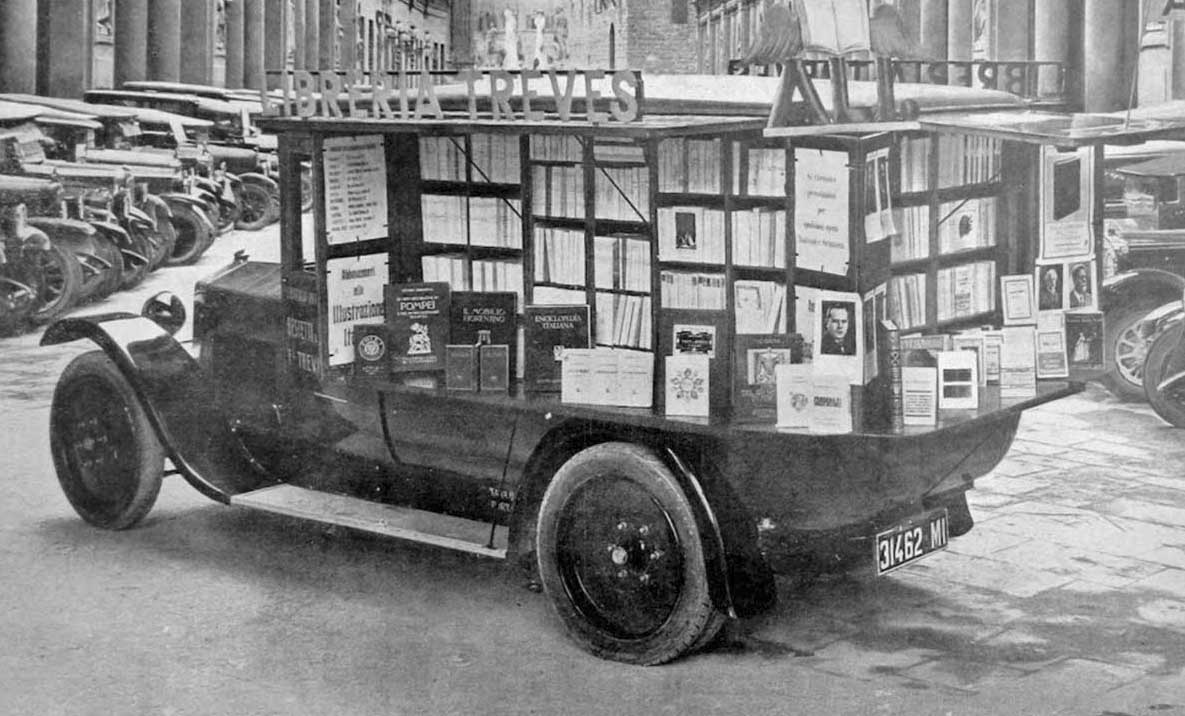

The Treves publishing house had established a series of pop-up kiosks, bookstores on wheels, and fancy books fair stands in various Italian cities from Turin to Palermo. In 1927, the Futurist artist Fortunato Depero designed the publisher’s stand at the Modena Bookfair.

With the new partnership, the company sought to expand its market to the Americas and hired Andrea Ragusa to travel to New York and Buenos Aires and offer the Italian Encyclopedia Treccani to Italians abroad. By then, cultural activity was also a powerful tool in the hands of the fascist dictatorship.

As a Sicilian, Ragusa had experienced the unification of Italy from a different viewpoint. After a brief compulsory career in the Italian Army that posted him on the Alps, as it was often the case to “italianize” Southerners, he married an Austrian woman with whom he had two daughters. Ragusa was driven by a profound love for books as well as a certain detachment from Italy and nationalism. He accepted the position gladly and left for New York, where he arrive in the wake of the Great Depression.

By 1933, Ragusa gave up on the Treccani project and bought a bookstore in New York that had been opened in 1864 by another Sicilian immigrant: Sante Fortunato Vanni.

After Guido Treves’ death in 1932, his wife Antoinetta reconstituted the new “Casa Editrice Treves” that operated until 1938. The racial laws stripped Jews of their civil rights and removed them from the publishing industry as well as from libraries. The firm was taken over by Aldo Garzanti and the name Treves was obliterated.

Aftermath

Emilio Treves came of age at a time of turmoil and enthusiasm in which Europe appeared heading toward an era of profound changes and social progress. It was a time when national ideals replaced religion and youth foresaw the possibility of a different and better world. Treves saw his publishing work as a means to “develop intelligence and form the rectitude of minds,” and wanted to “place Italian youth in an international context through major foreign novels”.

He was a tireless worker who spent his days and nights in full swing; he personally read all the manuscripts, criticized, and discussed them with the authors. He was known to be direct and to scold employees for their mistakes, for which he earned the nickname “l’orco”. He never held a grudge and was often cheerful and ironic. His tireless fervor, intelligence, and curiosity led him to surround himself with the most important Italian writers of the time, whom he supported unconditionally.

For 15 years, he held the position of President of the National Federation of Printers and Publishers, transferring its headquarter from Florence to Milan, and restoring the organization to a sound footing. He was also vice president of the Italian author society, SIAE, and a tenacious advocate of the protection of intellectual property and copyright in Italy.

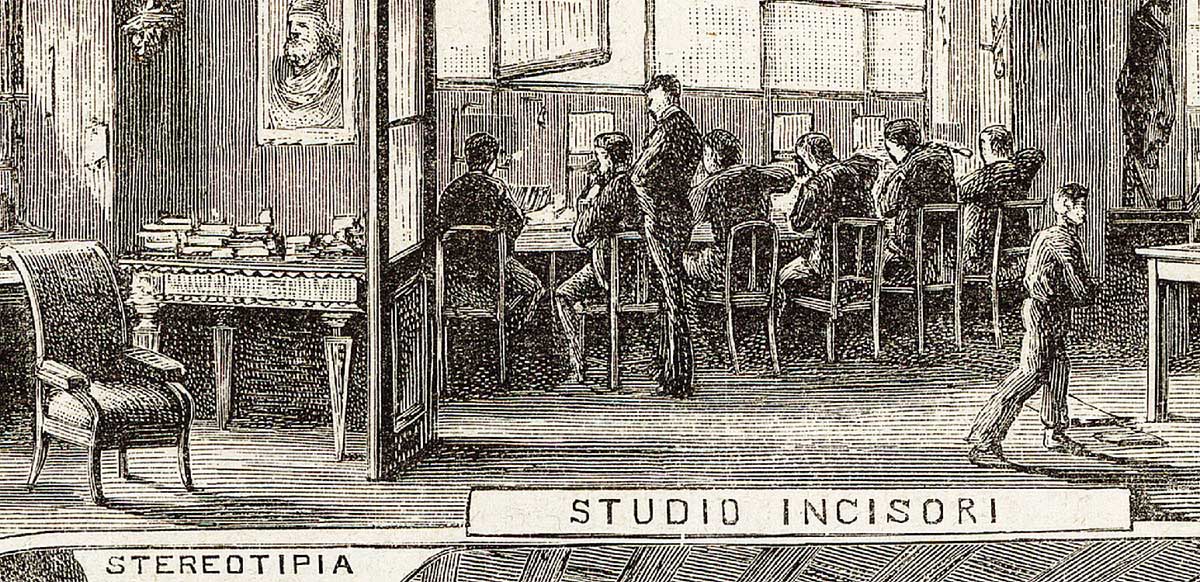

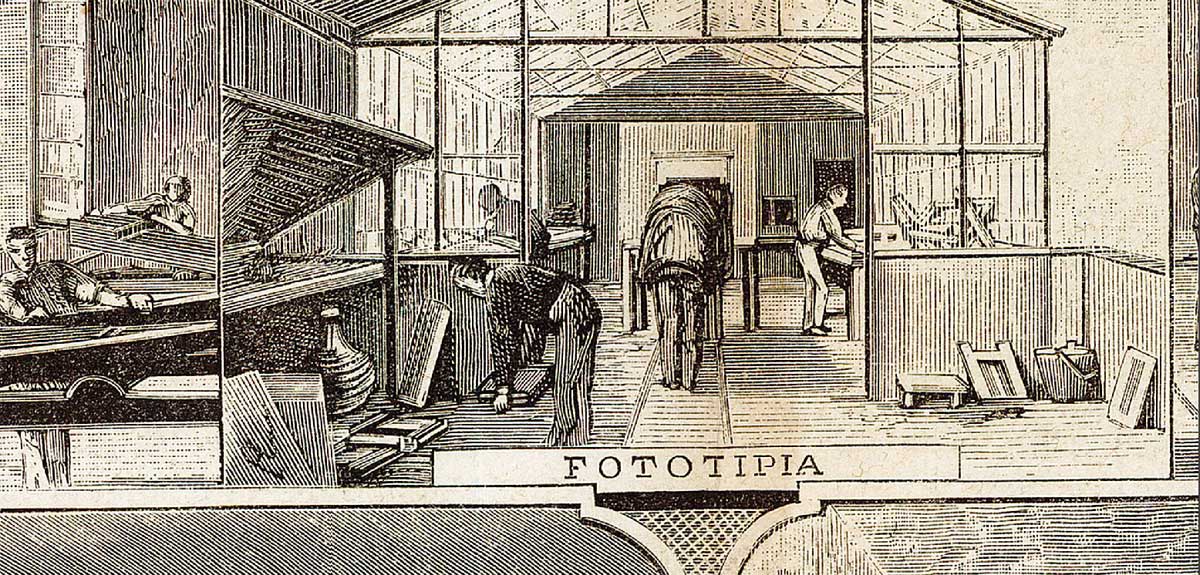

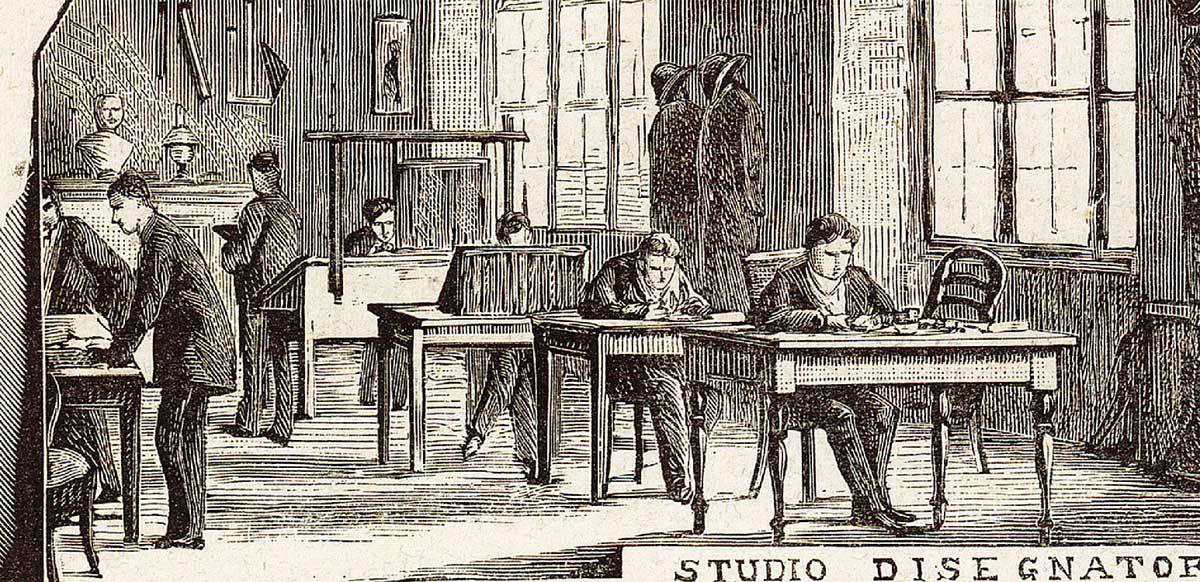

The Treves Publishing House, Courtesy Sergio Trippini

The Treves brothers’ contribution to Italian literature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was instrumental to the coming together of disparate traditions, aspirations, and sensibilities of post-unification Italy. Some of the most influential writers of the time gained recognition through their activity. These include Giovanni Verga, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Edmondo De Amicis, and Luigi Pirandello.

The Treves are constantly associated with their literary production and translation of the best works of foreign literature, particularly into French and English. Since the beginning of the organization, their catalog featured such authors as Lev Tolstoy and Charles Dickens.

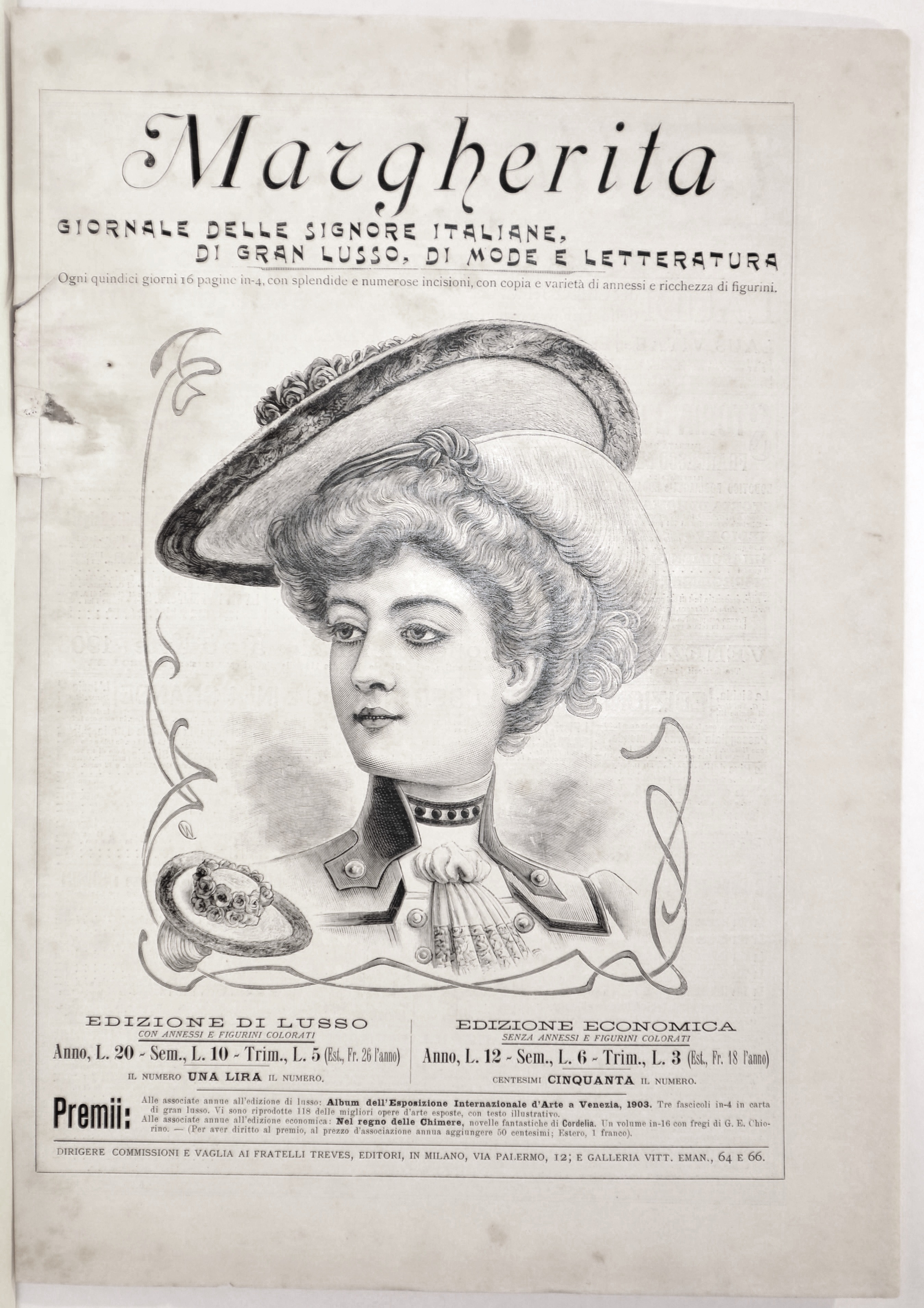

The Treves offered a penny pocket edition of works of fiction. In 1868, they began to publish The Bible in installments illustrated by Gustav Doré. Their commitment to provide education material to all is a defining trait of their work. Over the years, the Treves increased the number of magazines and journals aimed at new audiences, including the women’s magazine Margherita, and the beautifully illustrated children’s monthly Il Giornale dei Piccoli.