The Italian Rite

Adapted by Eitan Fiorino from the introduction to the Siddur Benè Roma by Rav Riccardo Di Segni

Italian Jews are under many respects an island in the Jewish world. Even the name of the land that has given them home for over twenty-two centuries was traditionally interpreted as a Hebrew word: I-tal-ya: “Island of the divine dew.” The liturgy of the Italian Jews sets them apart from all of the other communities in the Diaspora. Jewish liturgy is typically divided in two main categories, the Sephardic and Ashkenazic rites. The names of the two groups derive from their lands of origin, Spain and Germany, two major areas where Jewish civilization flourished in the Middle Ages. But this simple view does not account for the complexity of migratory currents of Jews and the presence of different Jewish groups in the same territory.

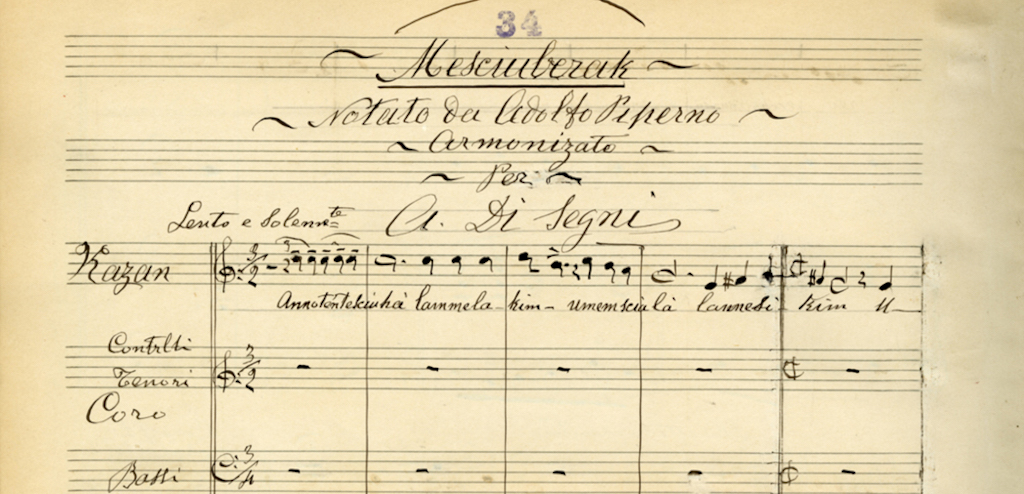

As a cultural and geographical crossroad, Italy has known most Jewish rituals and ethnic variations. However, the Italian communities have somewhat remained loyal to their particular nusach, prayer rite. Most notably Italian Jews have kept a unique set and order of prayers, cantillation style and original liturgical songs. They also developed their own specific legal codes, Judeo-Italian dialects and folkloric traditions that are not found elsewhere. The Italian rite represents a specific chapter in the Jewish liturgical world. Even though it is kept alive only by a small population spread between Italy, Israel and the Americas, it cannot be considered less important than the more commonly known representatives of the Jewish liturgy. This multilayered set of traditions, melodies, liturgical repertoire and cantillation style is known by different names: minhag Qahal Qadosh Roma (“of the sacred community of Rome”); minhag lo’ez or lo’azim (literally: “those who speak a foreign language”, probably in Latin); or minhag Benè Roma (“of the sons of Rome”), indicating the original centrality of Rome. It is currently maintained in Rome, Turin, and Milan, while in Florence and Venice it has merged with Sephardic and Ashkenazic traditions which imposed a different flavor. Until the Shoah, there were Italian synagogues in Mediterranean communities such as Salonica, but the devastation of those communities by the Nazis obliterated the last vestiges of Italian congregations that dated back hundreds of years. Today, outside of Italy, the Italian rite is only practiced in the Conegliano Synagogue in Jerusalem. The presence of Italian rabbis in cities including New York, Boston and Tokyo contributes to foster interest in this heritage.

To understand the Italian nusach, one must begin with a broad overview of the development of Jewish liturgy. Jewish prayer was, compared to the current day, less fixed and more variable during the Mishnaic and Talmudic eras. But during the Gaonic era (700 CE), a strong trend towards normalization of the liturgy and establishment of accepted practices emerged, leading to the development of a more fixed structure and set of prayers. At that time, one can identify in broad terms two distinct prayer rites – the Babylonian and Eretz Yisrael (Palestinian) liturgies – although the possibility that other distinct liturgies existed in the European and North African diasporas seems likely. From the great Babylonian academies came forth the first authoritative prayer books, the first of which was the Seder Rav ‘Amram, written in Babylonia in response to a query regarding the proper order of prayers originating in Spain. Meanwhile, despite the closeness and authority of the Geonic academies in Babylonia and their efforts to standardize the liturgy, the Jews in the land of Israel continued to maintain their own unique liturgical traditions.

It is commonly thought, in an undoubtedly oversimplified rubric, that the rite of the land of Israel migrated into Europe through Italy and Greece, and from Italy into Germany, carried by Jews moving northward from Italy into the Rhine valley, whereas the Babylonian rite moved locally in the Levant and, owing in large part to the Seder Rav Amram, into Spain – and in this manner, the Ashkenazic and Sephardic liturgies were established. But it is well known that eventually, the hegemony of the Babylonian academies prevailed, and the Eretz Yisrael nusach faded, leaving at most faint shadows in the liturgy. Some unique elements of the Italian rite are also sound in the prayer book of another Babylonian Gaon, that of Saadya. Saadya was born in Eretz Yisrael and lived in Egypt before emigrating to Babylonia, and it is therefore uncertain if the elements shared between the Italian rite and Saadya reflect a transmission of Saadya’s prayerbook from Babylonia to Italy, or rather a common origin in the old Eretz Yisrael rite.

By the Middle Ages, the prayer service had become relatively fixed, with a great number of relatively minor geographic variations across all areas of Jewish settlement – distinctive rites can be identified for Italy, Germany, France, Castille, Catalan, Greece, the Levant, Yemen and other areas of Jewish settlement. The development of the printing press further standardized the liturgy, as for the first time, prayerbooks became widely available – however, printing for wide distribution by its nature meant that some local variations would not be represented in the newly printed siddurim. With Italy at the forefront of Hebrew printing, among the first printed Hebrew texts was the Soncino prayerbook of the Italian rite, published in 1486.

With its central geographic location and, for the most part, relatively hospitable environment for Jewish life, Italian cities commonly (and in some cases to this day) housed synagogues adhering to a variety of prayer rites. In the north, communities of Ashkenazic and Italian Jews commonly lived side by side. Although Sephardim too lived in Italy, after the expulsion from Spain and southern Italy, great number of immigrant Jews created their own kehilot in many Italian cities. In Rome, for example, could be found synagogues adhering not only to the rite of the Italian Jews, but also to those of Jews from Castille, Catalan, Sicily and Germany. Although Italian Jews have clung to their distinctive liturgy even when outnumbered by Ashkenazim or Sephardim, in this environment, cross-fertilization in liturgical practices was inevitable. Thus, in spite of the perceivable distinction of the Italian rite today, when taking a closer look at it, we discover that through centuries of migrations and encounters, the original Italian canon has absorbed a significant amount of traits from other Jewish worlds. Neverteless, the Italian nusach retains much of its distinctive character that remains cherished by Italian Jews wherever they may live.

References

Rav Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal), Introduction (Mavò) to the Machazor benè Roma, Livorno 1856, 2

Daniel Goldschmidt, “Minhag benè Roma”, Tel Aviv 1965

I.Y.Kohn, “Bibliografia shel machazorim wesiddurè tefilla italiani”, in Mavò 1965

Italian Machazorim

Italian Machazor, Soncino e Casalmaggiore, 1485-86

Machazor di rito italiano secondo gli usi di tutte le Comunità, curated by Rav Menachem Emanuele Artom, Roma 1998-Jerusalem 2005

Italian Siddùr curated by Rav Panzieri, 1935

Siddur di rito italiano secondo l’uso delle Comunità di Roma e di Milano, curated by Rav Riccardo Di Segno and Rav Elia Richetti, Morashà Milano, 2002